ter nformation, ommunication & ducation work

Global Knowledge Network On Voter Education - learning from each other

Out of Country Voting in a Globalized World: What are the Implications?

An Introduction to Our Forthcoming Roundtable

Introduction

The issue of out of country voting (OCV) has risen to prominence lately, particularly in parts of Asia and Latin America. In response, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) has therefore from early 2017 taken preliminary steps to facilitate discussions among electoral management bodies, between those experienced in organizing OCV and those that are not. These discussions, initially through a roundtable discussion, will facilitate exchanges of practices and experiences on OCV, which would be of value to those countries planning on adopting it. It will also provide the opportunity for electoral management bodies (EMBs) to express and seek solutions to challenges that they face whenimplementing OCV. Any EMBs interested in participating are welcome to inform us.

The right to cast a vote in democratic electionsstand at the core of people's political rights. However, for citizens residing abroad the issue is less straight forward. Should people that have made a choice to live in another country still have voting rights in their home country? And if so, should the state be responsibilefor facilitating their vote from abroad – or should citizens simply have the option of coming home to exercise their right? These questions prompted International IDEA to publish its Handbook entitled, "Voting from Abroad", in 2007 and are still relevant today.

The right to cast a vote in democratic electionsstand at the core of people's political rights. However, for citizens residing abroad the issue is less straight forward. Should people that have made a choice to live in another country still have voting rights in their home country? And if so, should the state be responsibilefor facilitating their vote from abroad – or should citizens simply have the option of coming home to exercise their right? These questions prompted International IDEA to publish its Handbook entitled, "Voting from Abroad", in 2007 and are still relevant today.

In today's globalized world, international migration flows are prompting a debate around OCV. In 2015, there was a total of 244 million international migrants worldwide. In other words – one out of every 30 persons in the world is an international migrant. According to UN reports, almost half of the world's international migrants come from Asia. Five of the ten countries with most emigrants worldwide are located in Asia: India, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan and the Philippines. Looking at the list of countries it comes as no surprise that a solid majority – around 150 million – of today's international migrants are labour migrants.

What is "voting from abroad"?

International IDEA's Handbook on Voting from Abroad(2007: 8) defines OCVas:

Procedures which enable some or all electors of a country who are temporarily or permanently outside the country to exercise their voting rights from outside the national territory.

Implementing OCV requires careful considerations towards eligibility and voter registration requirements, the types of elections applicable and the voting methods available.

Eligibility requirements: Out of country voting eligibility requirements differ across countries. Some countries have opted for a restrictive approach whereby only citizens that reside outside their home country in an official capacity, i.e. diplomatic staff, public officials and military personnel (and their families), are allowed to vote from abroad. In other countries, there are no restrictions on eligibility, which means that also other categories of citizens abroad, such as labour migrants, refugees, students and others, are in principle allowed to vote. In between theserestrictive and more generous or open approach, there are a number of different arrangements.

Notably, holding citizenship is a minimum requirement for obtaining voting rights. If voter apply for and receive citizenship in their new country of residence and if this country prohibits double citizenship, the voter will, through loosing home country citizenship, also loose the right to vote in their home country.

Voter registration requirements: More often than not, citizens abroad who are eligible to take part in an election in their home country are required to register to vote. Registration process requirements – linked to registration modality (in particular in-person versus distance registration), location and period of registration as well as identification documentation requirements – are likely to impact on the level of abroad voter access.

Types of elections: OCV may be applicable to different types of elections. The most common practice is to allow abroad voters to take part in national elections, i.e. in presidential and/or parliamentary elections. Some countries also allow citizens to take part in sub-national (regional/provincial/local) and supra-national (regional parliamentary bodies, e.g. EU and Andean parliaments) elections.

Voting methods: The four main methods for OCV available are personal voting, postal voting, proxy voting and e-voting. These methods differ substantially when it comes to preparations, logistics and administration. When choosing a method, there is tension between the degree of control or supervision that the institution responsible can exercise and the degree of voter access. For example, personal voting, e.g. in diplomatic missions or similar facilities established for the specific purpose of the vote, is likely to enhance control, whereas distance voting through proxy, the post or the internet is likely to increase access.

Why allow vote from abroad – or why not?

Supporters of OCV argue that it is a basic human right of political participation. Through participating in elections, citizens abroad have an opportunity to, through political means, contribute to development at home which might impact their choices regarding where to live. Citizens living abroad often maintain close relationships with their home country and continue perceiving themselves as "belonging there".

Supporters also point to the economic impact of migration. In 2015, remittances flows were estimated to approach USD 600 billion globally and more than 70 percent was received in developing countries. In other words, citizens residing abroad are contributing to economic development at home and in some countries remittances make up a considerable share of the national GDP. In Tajikistan and Nepal, for example, remittances account for 42 and 29 percent of the GDP.

Lastly, OCV can also be seen as "high politics". The main example is when Turkey introduced OCV, it was not only "a purely domestic political matter, but a part of Turkey's increasingly contentious foreign relations."

However, it has also been argued that OCV gives citizens abroad undue influence over home country politics and development. Generally, citizens abroad, particularly those residing abroad for a longer period of time, are not directly affected by political decisions concerning a number of policy areas, such as road constructions, rural development and education to name a few.

Moreover, citizens abroadmay not pay taxes and thus, do not contribute directly to the state coffer. This argument was made by the Irish Government inthe 1990s when debating overseas voting rights, with the slogan"no representation without taxation". The size of diaspora populations has also featured the debate. In countries with large proportions of citizens abroad, it has been argued that OCV would allow for a situation by which citizens abroad to "swing the vote" and thus determine political and developmental trajectories in their home country. In countries where elections on the "main land" are very close, even a small number of abroad votes can tilt the results. In 2016, several reports discussed how the estimated 8 million Americans abroad could potentially tilt the US presidential elections and an anti-Trump activist group produced a software tool to simplify abroad registration processes assuming Americans abroad were largely Democrats. Whilst noting that the number of abroad voters can be large, a Council of Europe report dismissed the "public fear of a hypothetical mass invasion of electors from abroad" and urged countries to take on a more "realistic perspective" in making decisions on OCV.

A country's administrative and financial capacity may also impact on a country's decision to allow voters abroad to participate in elections. Experience shows that OCV is a huge administrative task with substantial costs. Notably, turnout among out of country voters remain low, which brings value-for-money considerations into play: some countries simply cannot afford going in this direction.

At the end of the day, the decision to allow OCV often comes down to politics. It is the legislators in the parliament that determine whether or not citizens residing outside their country's borders will have the right to cast their vote. Decisions on whether or not to allow OCV may be influenced by the self-interests of political majorities and their perception of the political choice of those living abroad. It is often assumed that those moving abroad do so because they are dissatisfied with political life or lack of economic opportunities at home. In other words, they are perceived to be inclined to vote against the government of the day, who is responsible for the current political and socio-economic conditions.

Global outlook

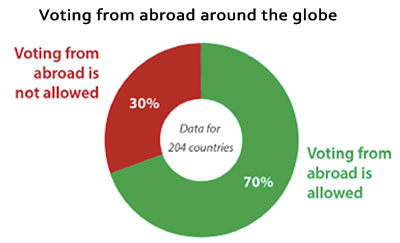

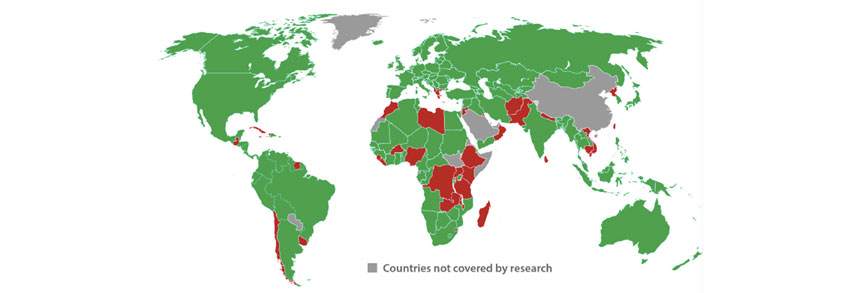

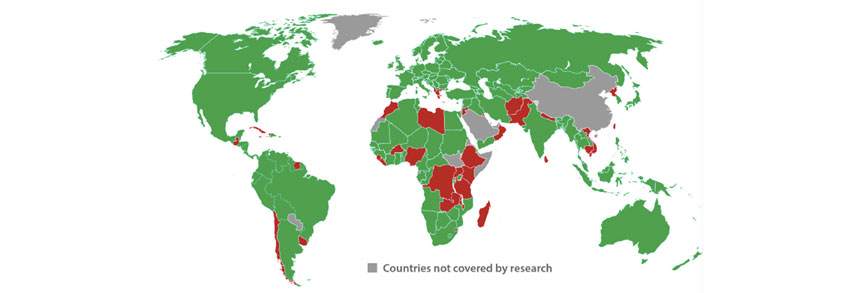

International IDEA's Voting from Abroad Database explores legal provisions for OCV in 216 countries and territories around the world. Altogether 114 countries and 77 territories allow people abroad to take part in legislative and/or presidential elections, respectively. Only 26 countries open sub-national elections up for participation outside the borders. In addition, 54 countries and territories allow citizens overseas to take part in referenda.

The voting methods offered differ considerably across countries.Personal voting is applied in 103 countries and territories (e.g. Brazil, Egypt, Finland, Mongolia, Myanmar, South Africa); postal in 51 (e.g. Austria, Bangladesh, Canada, El Salvador, Germany, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea); proxy voting in 18 (e.g. Belize, Mauritius, Vanuatu); and e-voting in 8 (e.g. Armenia).

Many countries allow voters abroad to choose from multiple voting methods. In Australia, Denmark, Japan, Latvia and Thailand, citizens abroad can choose between personal and postal voting. A combination of postal and proxy voting is applied in France, India, Netherlands and the UK. In Estonia and Switzerland, abroad voters can vote in person, by post or cast their ballot via the Internet. In Panama, citizens outside must vote either by post or via the Internet. In Poland and New Zealand, voters can even cast their vote by fax.

Many countries allow voters abroad to choose from multiple voting methods. In Australia, Denmark, Japan, Latvia and Thailand, citizens abroad can choose between personal and postal voting. A combination of postal and proxy voting is applied in France, India, Netherlands and the UK. In Estonia and Switzerland, abroad voters can vote in person, by post or cast their ballot via the Internet. In Panama, citizens outside must vote either by post or via the Internet. In Poland and New Zealand, voters can even cast their vote by fax.

In Asia, 29 countries and territories – or 67 percent of those that organize elections – allow citizens abroad to vote in legislative elections (see Annex A). Of these, in 19 of the 22 presidential systems (86%) in which presidents are popularly elected, citizens abroad can participate. Looking at voting methods in use, 25 countries apply personal voting, 8 countries postal voting, 3 countries e-voting and 1 country allows voters to vote by proxy. In-person voting is the method most frequently applied method in Asia: in 22 countries and territories, there is only one voting method in place and in 19 of these voters must cast their vote in person. Examples include Israel, Mongolia, Myanmar, Singapore, South Korea and Turkey. In seven cases, out of country voters can choose between two different voting methods. Looking at the countries that organize elections, 13 do not allow for OCV in any type of election2.

1The five countries that do not organize elections are: Brunei, China, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

2Countries/territories where abroad voters are not allowed to take part in any elections includes Afghanistan, Cambodia, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Nepal, Northern Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Palestinian Occupied Territories, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Vietnam.

Why discuss OCV now?

Several decades of globalization have transformed society into a 'global one'. People not only migrate, but they migrate more often – moving from country to country until they decide to settle in a country or move back to their original country. Moreover, communication barriers have fallen with the rise of the internet and mobile communications. All of these factors have prompted debates regarding the enfranchisement of citizens abroad and OCV rights.

The jury is still out on whether or not enfranchisement of citizens abroad is the best way to solve their under-representation citing the aforementioned problems. Countries that allow OCV still face administrative, financial and turnout challenges, which may be too much to bear for countries that aspire to go down the same route. Through exchanges and discussions that we shall promote together, challenges may be mapped out and solutions thereof may be explored. We look forward to seeing you at the Roundtable Discussion.

The right to cast a vote in democratic electionsstand at the core of people's political rights. However, for citizens residing abroad the issue is less straight forward. Should people that have made a choice to live in another country still have voting rights in their home country? And if so, should the state be responsibilefor facilitating their vote from abroad – or should citizens simply have the option of coming home to exercise their right? These questions prompted International IDEA to publish its Handbook entitled, "Voting from Abroad", in 2007 and are still relevant today.

The right to cast a vote in democratic electionsstand at the core of people's political rights. However, for citizens residing abroad the issue is less straight forward. Should people that have made a choice to live in another country still have voting rights in their home country? And if so, should the state be responsibilefor facilitating their vote from abroad – or should citizens simply have the option of coming home to exercise their right? These questions prompted International IDEA to publish its Handbook entitled, "Voting from Abroad", in 2007 and are still relevant today.

In today's globalized world, international migration flows are prompting a debate around OCV. In 2015, there was a total of 244 million international migrants worldwide. In other words – one out of every 30 persons in the world is an international migrant. According to UN reports, almost half of the world's international migrants come from Asia. Five of the ten countries with most emigrants worldwide are located in Asia: India, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan and the Philippines. Looking at the list of countries it comes as no surprise that a solid majority – around 150 million – of today's international migrants are labour migrants.

What is "voting from abroad"?

International IDEA's Handbook on Voting from Abroad(2007: 8) defines OCVas:

Procedures which enable some or all electors of a country who are temporarily or permanently outside the country to exercise their voting rights from outside the national territory.

Implementing OCV requires careful considerations towards eligibility and voter registration requirements, the types of elections applicable and the voting methods available.

Eligibility requirements: Out of country voting eligibility requirements differ across countries. Some countries have opted for a restrictive approach whereby only citizens that reside outside their home country in an official capacity, i.e. diplomatic staff, public officials and military personnel (and their families), are allowed to vote from abroad. In other countries, there are no restrictions on eligibility, which means that also other categories of citizens abroad, such as labour migrants, refugees, students and others, are in principle allowed to vote. In between theserestrictive and more generous or open approach, there are a number of different arrangements.

Notably, holding citizenship is a minimum requirement for obtaining voting rights. If voter apply for and receive citizenship in their new country of residence and if this country prohibits double citizenship, the voter will, through loosing home country citizenship, also loose the right to vote in their home country.

Voter registration requirements: More often than not, citizens abroad who are eligible to take part in an election in their home country are required to register to vote. Registration process requirements – linked to registration modality (in particular in-person versus distance registration), location and period of registration as well as identification documentation requirements – are likely to impact on the level of abroad voter access.

Types of elections: OCV may be applicable to different types of elections. The most common practice is to allow abroad voters to take part in national elections, i.e. in presidential and/or parliamentary elections. Some countries also allow citizens to take part in sub-national (regional/provincial/local) and supra-national (regional parliamentary bodies, e.g. EU and Andean parliaments) elections.

Voting methods: The four main methods for OCV available are personal voting, postal voting, proxy voting and e-voting. These methods differ substantially when it comes to preparations, logistics and administration. When choosing a method, there is tension between the degree of control or supervision that the institution responsible can exercise and the degree of voter access. For example, personal voting, e.g. in diplomatic missions or similar facilities established for the specific purpose of the vote, is likely to enhance control, whereas distance voting through proxy, the post or the internet is likely to increase access.

Why allow vote from abroad – or why not?

Supporters of OCV argue that it is a basic human right of political participation. Through participating in elections, citizens abroad have an opportunity to, through political means, contribute to development at home which might impact their choices regarding where to live. Citizens living abroad often maintain close relationships with their home country and continue perceiving themselves as "belonging there".

Supporters also point to the economic impact of migration. In 2015, remittances flows were estimated to approach USD 600 billion globally and more than 70 percent was received in developing countries. In other words, citizens residing abroad are contributing to economic development at home and in some countries remittances make up a considerable share of the national GDP. In Tajikistan and Nepal, for example, remittances account for 42 and 29 percent of the GDP.

Lastly, OCV can also be seen as "high politics". The main example is when Turkey introduced OCV, it was not only "a purely domestic political matter, but a part of Turkey's increasingly contentious foreign relations."

However, it has also been argued that OCV gives citizens abroad undue influence over home country politics and development. Generally, citizens abroad, particularly those residing abroad for a longer period of time, are not directly affected by political decisions concerning a number of policy areas, such as road constructions, rural development and education to name a few.

Moreover, citizens abroadmay not pay taxes and thus, do not contribute directly to the state coffer. This argument was made by the Irish Government inthe 1990s when debating overseas voting rights, with the slogan"no representation without taxation". The size of diaspora populations has also featured the debate. In countries with large proportions of citizens abroad, it has been argued that OCV would allow for a situation by which citizens abroad to "swing the vote" and thus determine political and developmental trajectories in their home country. In countries where elections on the "main land" are very close, even a small number of abroad votes can tilt the results. In 2016, several reports discussed how the estimated 8 million Americans abroad could potentially tilt the US presidential elections and an anti-Trump activist group produced a software tool to simplify abroad registration processes assuming Americans abroad were largely Democrats. Whilst noting that the number of abroad voters can be large, a Council of Europe report dismissed the "public fear of a hypothetical mass invasion of electors from abroad" and urged countries to take on a more "realistic perspective" in making decisions on OCV.

A country's administrative and financial capacity may also impact on a country's decision to allow voters abroad to participate in elections. Experience shows that OCV is a huge administrative task with substantial costs. Notably, turnout among out of country voters remain low, which brings value-for-money considerations into play: some countries simply cannot afford going in this direction.

At the end of the day, the decision to allow OCV often comes down to politics. It is the legislators in the parliament that determine whether or not citizens residing outside their country's borders will have the right to cast their vote. Decisions on whether or not to allow OCV may be influenced by the self-interests of political majorities and their perception of the political choice of those living abroad. It is often assumed that those moving abroad do so because they are dissatisfied with political life or lack of economic opportunities at home. In other words, they are perceived to be inclined to vote against the government of the day, who is responsible for the current political and socio-economic conditions.

Global outlook

International IDEA's Voting from Abroad Database explores legal provisions for OCV in 216 countries and territories around the world. Altogether 114 countries and 77 territories allow people abroad to take part in legislative and/or presidential elections, respectively. Only 26 countries open sub-national elections up for participation outside the borders. In addition, 54 countries and territories allow citizens overseas to take part in referenda.

The voting methods offered differ considerably across countries.Personal voting is applied in 103 countries and territories (e.g. Brazil, Egypt, Finland, Mongolia, Myanmar, South Africa); postal in 51 (e.g. Austria, Bangladesh, Canada, El Salvador, Germany, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea); proxy voting in 18 (e.g. Belize, Mauritius, Vanuatu); and e-voting in 8 (e.g. Armenia).

Many countries allow voters abroad to choose from multiple voting methods. In Australia, Denmark, Japan, Latvia and Thailand, citizens abroad can choose between personal and postal voting. A combination of postal and proxy voting is applied in France, India, Netherlands and the UK. In Estonia and Switzerland, abroad voters can vote in person, by post or cast their ballot via the Internet. In Panama, citizens outside must vote either by post or via the Internet. In Poland and New Zealand, voters can even cast their vote by fax.

Many countries allow voters abroad to choose from multiple voting methods. In Australia, Denmark, Japan, Latvia and Thailand, citizens abroad can choose between personal and postal voting. A combination of postal and proxy voting is applied in France, India, Netherlands and the UK. In Estonia and Switzerland, abroad voters can vote in person, by post or cast their ballot via the Internet. In Panama, citizens outside must vote either by post or via the Internet. In Poland and New Zealand, voters can even cast their vote by fax. In Asia, 29 countries and territories – or 67 percent of those that organize elections – allow citizens abroad to vote in legislative elections (see Annex A). Of these, in 19 of the 22 presidential systems (86%) in which presidents are popularly elected, citizens abroad can participate. Looking at voting methods in use, 25 countries apply personal voting, 8 countries postal voting, 3 countries e-voting and 1 country allows voters to vote by proxy. In-person voting is the method most frequently applied method in Asia: in 22 countries and territories, there is only one voting method in place and in 19 of these voters must cast their vote in person. Examples include Israel, Mongolia, Myanmar, Singapore, South Korea and Turkey. In seven cases, out of country voters can choose between two different voting methods. Looking at the countries that organize elections, 13 do not allow for OCV in any type of election2.

1The five countries that do not organize elections are: Brunei, China, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

2Countries/territories where abroad voters are not allowed to take part in any elections includes Afghanistan, Cambodia, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Nepal, Northern Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Palestinian Occupied Territories, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Vietnam.

Why discuss OCV now?

Several decades of globalization have transformed society into a 'global one'. People not only migrate, but they migrate more often – moving from country to country until they decide to settle in a country or move back to their original country. Moreover, communication barriers have fallen with the rise of the internet and mobile communications. All of these factors have prompted debates regarding the enfranchisement of citizens abroad and OCV rights.

The jury is still out on whether or not enfranchisement of citizens abroad is the best way to solve their under-representation citing the aforementioned problems. Countries that allow OCV still face administrative, financial and turnout challenges, which may be too much to bear for countries that aspire to go down the same route. Through exchanges and discussions that we shall promote together, challenges may be mapped out and solutions thereof may be explored. We look forward to seeing you at the Roundtable Discussion.

Mette Bakken and Adhy Aman,

(International IDEA)